Sri Lanka’s agriculture industry is poised for a transformation. Like many developing countries, the sector today is characterized by small landholdings, low productivity and high post-harvest losses. Smallholder farmers struggle to consistently supply the quality and volumes demanded by modern markets. But change is on the horizon. Innovative new models like industry clustering and value chain upgrading provide pathways for smallholders to increase productivity, manage uncertainty, and capture larger profit shares. With the right mix of private sector partnership, government support and new thinking, Sri Lanka’s farmers could well become the driving force behind sustainable economic development.

- Introduction

This report provides a comprehensive overview of supply chain management, industry clustering, and value chain innovation in the context of Sri Lanka’s agriculture sector. It examines the challenges faced by smallholder farmers in Sri Lanka in detail, such as high transaction costs and uncertain demand. The report suggests clustering as a potential solution to help smallholder farmers achieve commercial scale. It also extensively discusses various methods for adding value in agricultural supply chains through product, process, and institutional innovations.

- Supply Chains and Governance Mechanisms

A supply chain encompasses the end-to-end process of producing, distributing and selling a product or service to an end consumer. It covers all the steps from raw material sourcing through production, warehousing, transportation, retailing and finally reaching the end customer. Effective supply chain management requires coordinating activities and aligning incentives across multiple firms in the chain to maximize efficiency.

There are three main governance mechanisms that can be used to coordinate transactions within a supply chain:

- Market-based transactions have simple contracts and price competition as the governing mechanism. This is suitable for commodity products with low complexity and easily specified contracts.

- Firm-based transactions rely on command, control and detailed employment contracts within a vertically integrated firm. This is suitable for highly complex transactions with high uncertainty and very incomplete contracts.

- Supply chain transactions use relational contracts and reputation mechanisms as governance, with a medium level of contract completeness. Ongoing relationships between buyers and suppliers allow adaptations over time.

The choice of governance mechanism depends on the transaction complexity, uncertainty and ability to codify contracts. More integrated supply chains are preferred for products with high intangibility, specificity and contract incompleteness to improve coordination and information sharing.

- Challenges Facing Smallholder Farmers in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s agriculture sector is characterized by small landholdings of less than 2-4 acres and traditional natural cultivation methods. Most agricultural production happens through home gardens focused on self-sufficiency, with surplus production sold locally.

This natural economy faces several challenges in reliably supplying modern market channels like supermarkets and exports, which have more stringent, standardized quality requirements and expectations of timely delivery and food safety:

- High transaction costs for collection and distribution through multiple small, dispersed farms. Collectors need to cover long distances to gather small volumes from each farm.

- Uncertain and highly erratic demand in local rural markets and roadside stalls, leading to high post-harvest losses. Retailers experience low sales turnover due to small local population bases.

- Weak bargaining power of individual smallholder farmers versus consolidated large-scale collectors and retailers. Farmers receive extremely low prices that demotivate investments.

- Limited investment in quality improvements, packaging, branding and post-harvest management due to limited profit margins. Products are sold loose without grading.

- Overall impact is a vicious cycle of low productivity, high food losses, high marketing margins but low profits for small farmers.

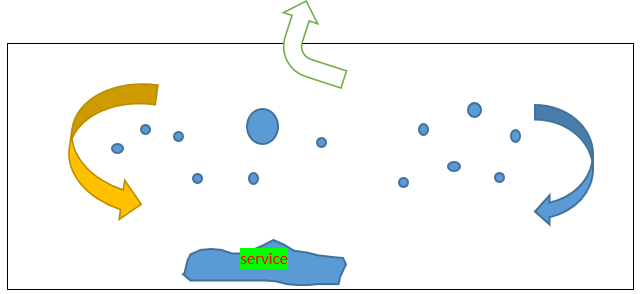

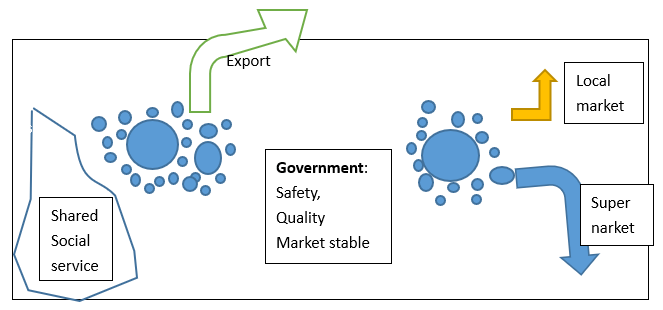

- Industry Clustering as a Potential Solution

Clustering refers to a geographic concentration of smallholder producers engaged in the same or related agricultural activities in a particular area. A cluster provides functional integration even while farmers maintain independent ownership. Potential benefits include:

- Specialization and knowledge sharing between farmers located close together. Farmers can focus on a limited number of crops and access knowledge spillovers.

- Lower transaction costs for provision of inputs, collection, storage, transport, packaging and other services due to economies of scale. Service providers are drawn to clusters.

- Development of long-term, stable supply relationships and associated reputation mechanisms between farmers, collectors, processors etc.

- Achieving scale required for modern market access through collective action. Products can be pooled to meet large orders.

Key enablers for the emergence of successful, sustainable clusters include:

- Presence of a pillar crop in which the area holds a strong comparative advantage, such as banana cultivation in Hambantota.

- Stable external demand from exports, supermarkets or value-added processors, which incentivizes cluster formation to reduce costs.

- Presence of some large, commercially oriented anchor farms that can play a leading role in dissemination of technologies and market linkages.

- Shared infrastructure and services like cold storage units, packaging centers, and transport systems.

- Supportive government policies to facilitate land use, provide infrastructure, mediate trade relationships and maintain stability.

Overall, clustering enables smallholder farmers to integrate into modern, commercial value chains more effectively while retaining independence. Specialization, collective strength and shared services help overcome scale constraints.

- Methods for Value Addition in Agricultural Supply Chains

Value addition involves modifying raw agricultural materials through various methods to increase their perceived usefulness and value to end consumers. This generates higher incomes for producers by capturing a larger portion of the end consumer expenditure. Main methods for value addition include:

- Product innovation through food processing, packaging, branding, embedding additional features etc. to create new products that fetch premium prices.

- Process improvements like cold storage technologies, pre-processing (grading, sorting, cleaning), controlled ripening techniques and other post-harvest processes that improve quality consistency and reduce losses.

- New business models like direct farmer-consumer links through IT-enabled platforms that increase pricing power for farmers. Models that funnel credit, inputs and know-how to smallholders also add value.

- Vertical integration by food and agribusiness companies allows tighter coordination in the chain and capturing of value addition at multiple stages.

- Use of agricultural by-products and wastes as inputs for energy production or conversion into economical cattle feed through compaction etc.

- Supply chain optimization by removing unnecessary high-cost intermediaries, duplication of efforts or activities that don’t contribute to end-consumer value.

Crucially, value is derived from the perceived benefits to end-consumers rather than intermediate customers. Close understanding of changing consumer preferences and buying behavior is key. Value chain analysis should be anchored around identifying points of value creation for the ultimate consumer.

- Opportunities for Value Chain Innovation in Sri Lanka

Various opportunities exist for value chain upgrading and innovation to benefit smallholder farmers in Sri Lanka:

- Conversion of mango, pineapple and other fruit residues from processing into value-added products through drying, pulping etc. Currently residues have low value.

- Use of solar energy for irrigation, transportation, agricultural machinery etc. to reduce costs and promote food processing. Solar cold rooms and milk chillers are examples. Integrated design can maximize value.

- Reuse of agricultural wastes for energy production through biomass systems, and for conversion into cost-effective cattle feed through compaction, drying etc. Current reuse is limited.

- Plastic recycling systems to convert waste plastic into value-added products while improving environment. Potential for youth employment.

- New models based on linking equipment-intensive Chinese companies with Sri Lanka’s natural resources and strategic location. Could improve productivity and quality.

- Development of regional free trade zones with a focus on food processing and packaging for re-export. This can attract FDI into value addition activities.

- Conclusion

In summary, industry clustering and greater value addition in agricultural supply chains present important opportunities to uplift incomes of Sri Lanka’s smallholder farmers. Realizing these opportunities requires extensive collaboration between private sector partners, farmers, government agencies and innovation centers. With an appropriate enabling environment, transaction costs can be reduced, stable market linkages forged, and sustainable, modern value chains developed.

Leave a comment